“Going to the Doctor” is a common lesson theme in EFL textbooks. They tend, however, to have either a grammatical focus, e.g. practising ‘should’, or a vocabulary focus, illness vocabulary. Usually, of course, it is a combination of the two. However, the genre of the Doctor Consultation varies greatly from culture to culture and these differences and the genre expectations that are involved in visiting the doctor are not generally treated much in textbooks.

Even before the consultation, there are differing cultural expectations of where and when to seek help. Japan, for example, does not have the equivalent of a General Practitioner or family doctor. Every doctor specializes in a particular area, like internal medicine, or ear/nose & throat. So rather than visiting a G.P. who then refers you to a specialist, you effectively diagnose yourself and then go to the appropriate specialist. It is also much more common to go straight to the hospital, even for a cold. In England, on the other hand, you are required to register with a local practice and would be turned away from a hospital without a referral. It would be important, therefore, to explain the wider medical system in which the consultation takes place, something that textbooks rarely if ever take into account.

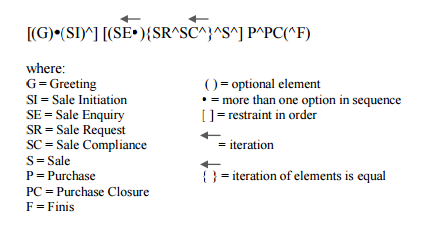

The basic genre stages of a medical consultation, as usually presented in textbooks, could be summarized as:

1. opening

2. complaint

3. examination or test

4. diagnosis

5. treatment or advice

6. closing

(http://www.paultenhave.nl/genre.htm)

Yet this has always felt somewhat too perfunctory. So based on the British Corpus it could in fact be extended to include:

- GREETING

- EXPLAIN PROBLEM (GENERAL)

- EXPLAIN SYMPTOMS (DETAILS)

- PAST HISTORY

- PLEA FOR HELP/ESTABLISH AUTHORITY

- EXAMINATION

- DIAGNOSIS (GENERAL)

- DIAGNOSIS (EXPLANATION)

- ADVICE/RECOMMENDATION

- JUSTIFICATION FOR RECOMMENDATION

- CONFIRMATION

- TREATMENT PROCEDURE

- WARNINGS

- RECONFIRM/REASSURANCE

- WRITE PRESCRIPTION

- CLOSE

Here is a Powerpoint (GOING TO THE DOCTOR’S) I use to demonstrate the differences between the stages.