The second part of the context of situation is the tenor of discourse. Tenor refers to:

who is taking part, to the nature of the participants, their statuses and roles: what kinds of role relationship obtain among the participants, including permanent and temporary relationships of one kind or another, both the type of speech role that they are taking on in the dialogue and the whole cluster of of socially significant relationships in which they are involved?

(Halliday & Hasan, 1985, p.12)

There are three basic factors within tenor:

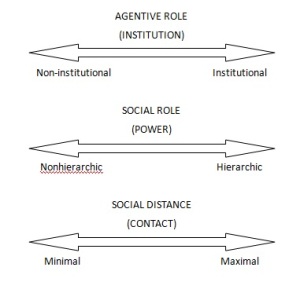

- agentive role, or the institutional (or not) roles of the participants, such as doctor/patient, teacher/student, etc.;

- social role, or the power relationship between them which may be hierarchic or nonhierarchic and includes expert/novice and also conferred social status and gender, etc.;

- social distance, or the amount or nature of contact the participants may have, which ranges from minimal (close friends) to maximal (formal settings).

Rather than an either/or situation, these tenor factors exist on a cline, as may be represented here:

It is also possible for these tenor relationships to change over time. A regular patient, for example, may have less social distance than one on a first-time visit. They may also be affected by field choices: an office-worker talking to their manager about football may use a different register than when requesting leave. This may also be affected by the context of culture with each factor given more or less value. In a Japanese work-place context (and in general) agentive and social roles have comparatively more prominence: even after years of close working contact (and even after retirement) many Japanese will continue to use formal work-place terms of address that encode these roles.