Here is the end of a 1-star review for a book which shall remain anonymous.

Why I bothered to read to the end still baffles me! The most irritating thing about the book was the incredible number of times language of today was used when the time was supposed to be centuries ago. RIDICULOUS!

The complaint that it used “language of today” is brings up an important point for learning a language. We of course have no idea how people really spoke centuries ago – we may have written sources but that is not necessarily how people spoke. What the reviewer actually means is that the writer did not use the language that we commonly expect to see in historical fantasy novels. This language is not from personal experience of the time, we do not have recordings from the 1400’s, but from our experience of reading other historical fantasy novels. It is a conventional language, one that has been stylistically formalized by countless writers of this fiction. The writing has certain elements of vocabulary and use of grammar that we as readers expect.

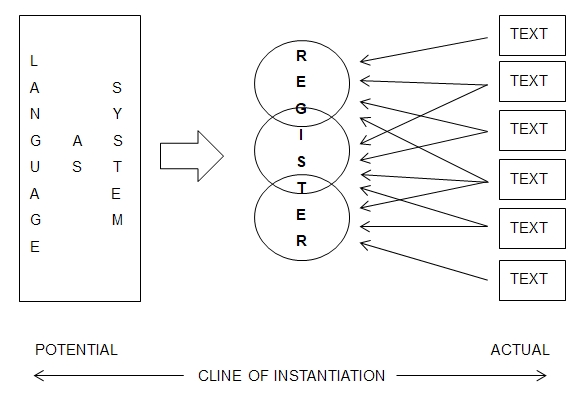

This patterning of lexico-grammar that we commonly associate with a particular situation is what we call register. Register is “the configuration of semantic resources that the member of a culture typically associates with a situation type” (Halliday, 1978). It is through register that we can easily recognize types of language use, e.g. scientific English, or a sports report. Every individual text is produced out of the range of options provided by the system of language, yet certain groups of texts within similar contexts display similar linguistic features and it is this that gives us the register. Also, as Matthiessen (2019) puts it, “the more specific the settings of parameters of field, tenor, and mode are within context, the more constrained the range of options in the semantic system will be”. In other words, if you have a very constrained context of situation, say for example, a legal contract agreement, there will be a corresponding constraint on the language choices available. Register (sometimes called text-type) thus lies midway on the cline of instantiation between system and instance. It may be represented as:

The importance of this for language learners is two-fold. First, it is common for language learners to ‘know’ a word or phrase but not how to use it. Learners may sound overly casual in formal situations or vice-versa. They are unable to adapt their language use to fit the situation. Or they may overextend the range of register of vocabulary. I remember being somewhat alarmingly instructed by a Japanese doctor to ‘expire’ until i realized that had taken an item from a ‘science: biology’ register and used it incorrectly in a ‘medicine: consultation’ register, and said expire/inspire instead of breathe out/breathe in.

Conversely, learners are often unable to recognize a particular register and be able to respond or react appropriately. Part of learning to read is learning to recognize differing text-types. An incongruity between register and situation is a commonly used trope in humor, as in this cartoon from the New Yorker:

A learner unfamiliar with ‘legalese’ would probably miss the joke.

Yet register is rarely taken into account in textbooks, where grammar and vocabulary is very often presented in a completely decontextualized situation. One textbook I used started every lesson with a short conversation, regardless of the usual context and register. It is difficult to see how a learner can get any sense of appropriate language use. In my own experience learning Japanese, grammar items were presented, and drilled, without any reference to when, where, or how it was actually used. However, this should really be the goal of helping learners to become competent and confident language users.